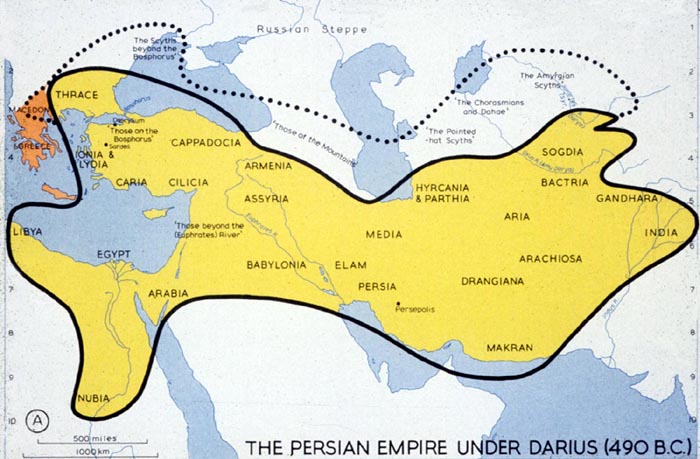

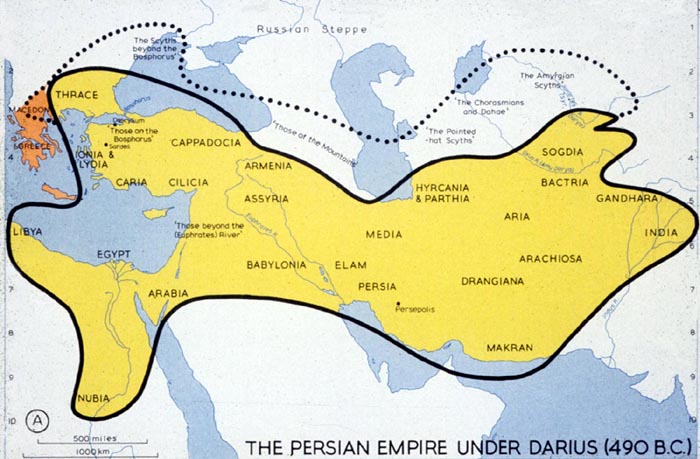

The Persian Empire, about 500 B.C.

Persian Timeline

The early history of man in Iran goes back well beyond the Neolithic period, it begins to get more interesting around 6000 BC, when people began to domesticate animals and plant wheat and barley. The number of settled communities increased, particularly in the eastern Zagros mountains, and handmade painted pottery appears. Throughout the prehistoric period, from the middle of the sixth millennium BC to about 3000 BC, painted pottery is a characteristic feature of many sites in Iran.

The First Persian State: Achaemenid Persia (648 BC-330 BC)

Cyrus the Great (559-529 BC)

"I am Cyrus, who founded the empire of the Persians.

Grudge me not therefore, this little earth that covers my body."

Cambyses II

Darius I - Darius the Great (521-486 BC)

The Stone Tablets of Darius the Great

The Persian Rosetta Stone

Seal of Darius the Great

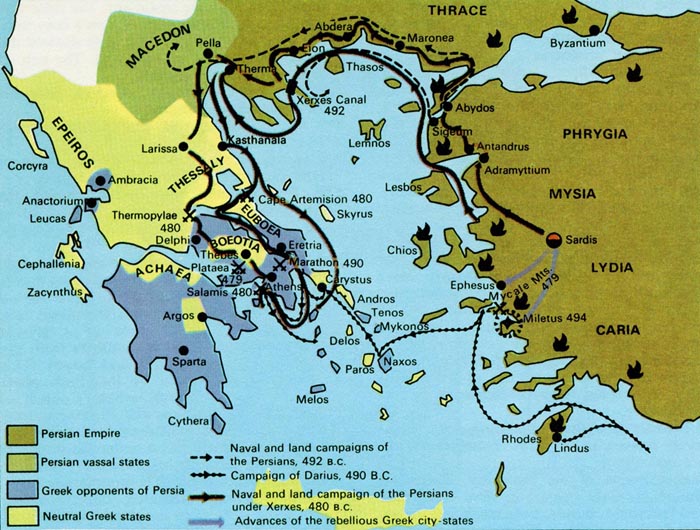

The Persian Wars

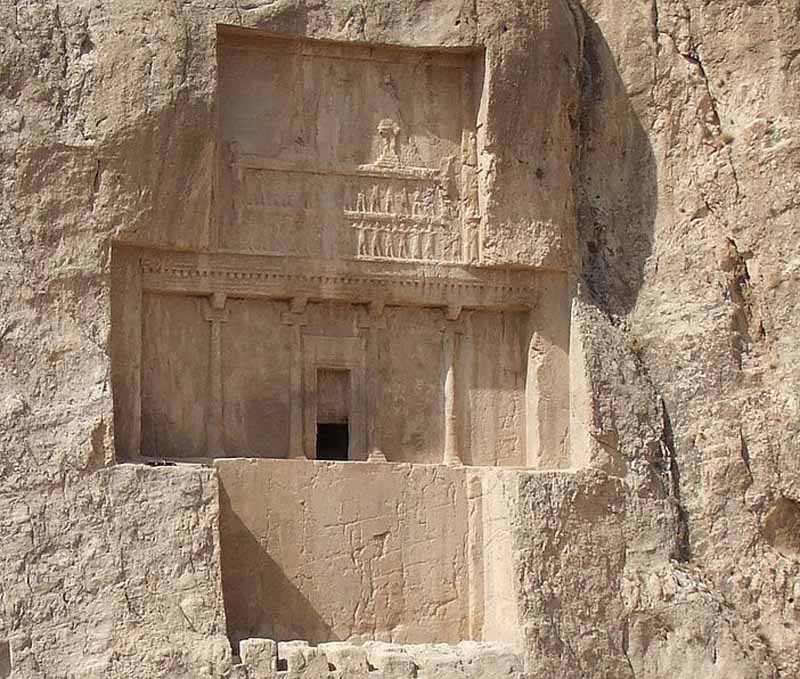

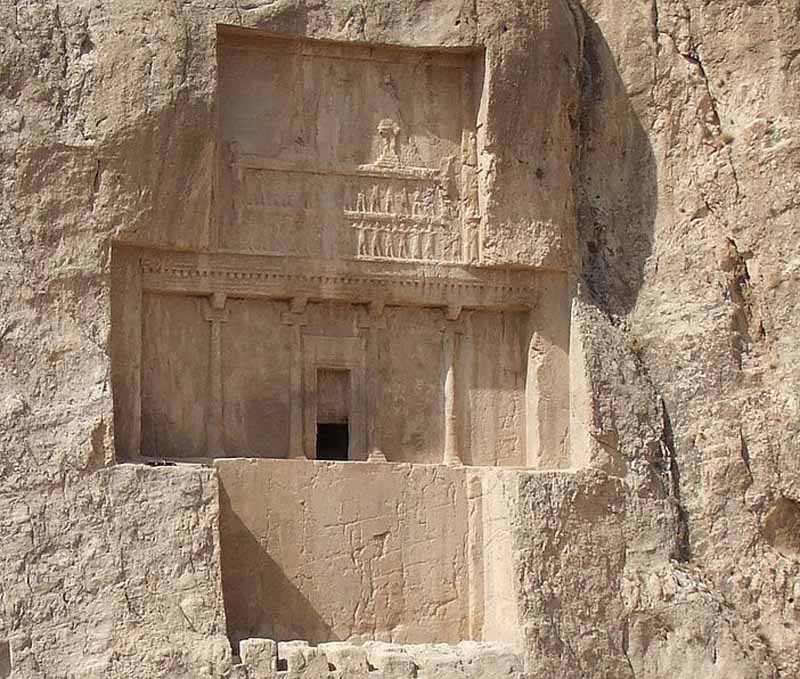

Tomb of Darius

Hellenistic Persia (330 BC-170 BC)

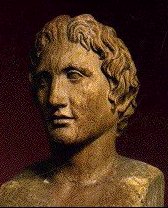

Alexander the Great, King of Macedonia

Parthian Persia (170 BC-AD 226)

Metallic statue of a Parthian prince (thought to be Surena), AD 100,

kept at The National Museum of Iran, Tehran.

Sassanid Persia (AD 226-650)

Head of king Shapur II (Sasanian dynasty 4th century AD).

Islam and Persia (650-1219)

Persia under the Mongols and their successors (1219-1500)

A New Persian Empire: The Safavids (1500-1722)

Persia and Europe (1722-1914)

Persia in World War One (1914-1918)

Persia after World War One (1919-1935)

References and Links:

Persian Empire

2000-1800 BC, Aryan migration from Southern Russia to Near East

Persia's earliest known kingdom was the proto-Elamite Empire followed by

The Medes

Deioces, 728BC - 675BC

Phraortes (Kashtariti?), 675BC - 653BC

Scythian interregnum

Cyaxares, 625BC - 585BC

Astyages, 585BC - 550BC

The Medes

Deioces, 728BC - 675BC

Phraortes (Kashtariti?), 675BC - 653BC

Scythian interregnum

Cyaxares, 625BC - 585BC

Astyages, 585BC - 550BC

628 BC, Birth of Zartosht, Zoroaster, the Persian Prophet

Achaemenid Dynasty

Achaemenes

Teispes

Cyrus I

Cambyses I (Kambiz)

Cyrus the Great, Start of Achaemenid Empire, 559BC -530BC

Kambiz II, 530BC - 522BC

Smerdis (the Magian), 522BC

Darius I the Great, 522BC - 486BC

Xerxes I (Khashyar), 486BC - 465BC

Artaxerxes I , 465BC - 425BC

Xerxes II, 425BC - 424BC (45 days)

Darius II, 423BC - 404BC

Artaxerxes II, 404BC - 359BC

Artaxerxes III, 359BC - 339BC

Arses, 338BC - 336BC

Darius III, 336BC - 330BC

Achaemenes

Teispes

Cyrus I

Cambyses I (Kambiz)

Cyrus the Great, Start of Achaemenid Empire, 559BC -530BC

Kambiz II, 530BC - 522BC

Smerdis (the Magian), 522BC

Darius I the Great, 522BC - 486BC

Xerxes I (Khashyar), 486BC - 465BC

Artaxerxes I , 465BC - 425BC

Xerxes II, 425BC - 424BC (45 days)

Darius II, 423BC - 404BC

Artaxerxes II, 404BC - 359BC

Artaxerxes III, 359BC - 339BC

Arses, 338BC - 336BC

Darius III, 336BC - 330BC

Hellenistic Period

Alexander (III), 330BC - 323BC

Philip III (Arrhidaeus), 323BC - 317BC

Alexander IV, 317BC - 312BC

Alexander (III), 330BC - 323BC

Philip III (Arrhidaeus), 323BC - 317BC

Alexander IV, 317BC - 312BC

Seleucids

Seleucus I, 312BC - 281BC

Antiochus I Soter, 281BC - 261BC (coregent)

Seleucus, 280BC - 267BC (coregent)

Antiochus II Theos, 261BC - 246BC

Sleucus II Callinicus, 246BC - 238BC

Seleucus I, 312BC - 281BC

Antiochus I Soter, 281BC - 261BC (coregent)

Seleucus, 280BC - 267BC (coregent)

Antiochus II Theos, 261BC - 246BC

Sleucus II Callinicus, 246BC - 238BC

The early history of man in Iran goes back well beyond the Neolithic period, it begins to get more interesting around 6000 BC, when people began to domesticate animals and plant wheat and barley. The number of settled communities increased, particularly in the eastern Zagros mountains, and handmade painted pottery appears. Throughout the prehistoric period, from the middle of the sixth millennium BC to about 3000 BC, painted pottery is a characteristic feature of many sites in Iran.

The Persian Empire is the name used to refer to a number of historic dynasties that have ruled the country of Persia (Iran). Persia's earliest known kingdom was the proto-Elamite Empire, followed by the Medes; but it is the Achaemenid Empire that emerged under Cyrus the Great that is usually the earliest to be called "Persian." Successive states in Iran before 1935 are collectively called the Persian Empire by Western historians.

The name 'Persia' has long been used by the West to describe the nation of Iran, its people, or its ancient empire. It derives from the ancient Greek name for Iran, Persis. This in turn comes from a province in the south of Iran, called Fars in the modern Persian language and Pars in Middle Persian. Persis is the Hellenized form of Pars, based on which other European nations termed the area Persia. This province was the core of the original Persian Empire. Westerners referred to the state as Persia until March 21, 1935, when Reza Shah Pahlavi formally asked the international community to call the country by its native name. Some Persian scholars protested this decision because changing the name separated the country from its past. It also caused some Westerners to confuse Iran with Iraq; so in 1959 his son Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi announced that both Persia and Iran can be used interchangeably.

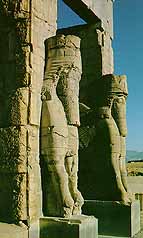

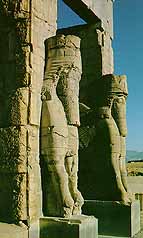

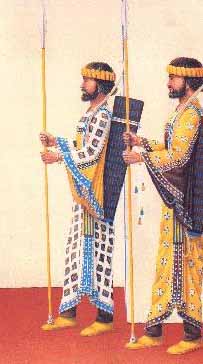

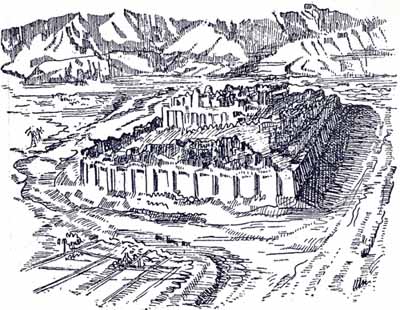

The Persian Empire dominated Mesopotamia from 612-330 BC. The Achaemenid Persians of central Iran ruled an empire which comprised Iran, Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt, and parts of Asia Minor and India. Their ceremonial capital was Persepolis in southern Iran founded by King Darius the Great. Persepolis was burned by Alexander the Great in 331 B.C. Only the columns, stairways, and door jambs of its great palaces survived the fire. The stairways, adorned with reliefs representing the king, his court, and delegates of his empire bringing gifts, demonstrate the might of the Persian monarch.

The first record of the Persians comes from an Assyrian inscription from c. 844 BC that calls them the Parsu (Parsuash, Parsumash) and mentions them in the region of Lake Urmia alongside another group, the Madai (Medes). For the next two centuries, the Persians and Medes were at times tributary to the Assyrians. The region of Parsuash was annexed by Sargon of Assyria around 719 BC. Eventually the Medes came to rule an independent Median Empire, and the Persians were subject to them.

The Achaemenids were the first line of Persian rulers, founded by Achaemenes (Hakaimanish), chieftain of the Persians around 700 BC.

Around 653 BC, the Medes came under the domination of the Scythians, and the son of Achaemenes, a certain Teispes, seems to have led the nomadic Persians to settle in southern Iran around this time -- eventually establishing the first organized Persian state in the important region of Anshan as the Elamite kingdom was permanently destroyed by the Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal (640 BC).

The kingdom of Anshan and its successors continued to use Elamite as an official language for quite some time after this, although the new dynasts spoke Persian, an Indo-Iranian tongue.

Teispes' descendants branched off into two lines, one line ruling in Anshan, while the other ruled the rest of Persia. Cyrus II the Great united the separate kingdoms around 559 BC.

Cyrus the Great (559-529 BC)

"I am Cyrus, who founded the empire of the Persians.

Grudge me not therefore, this little earth that covers my body."

At this time, the Persians were still tributary to the Median Empire ruled by Astyages.

Cyrus rallied the Persians together, and in 550 BC defeated the forces of Astyages, who was then captured by his own nobles and turned over to the triumphant Cyrus, now Shah of the Persian kingdom.

As Persia assumed control over the rest of Media and their large Middle Eastern empire, Cyrus led the united Medes and Persians to still more conquest. He took Lydia in Asia Minor, and carried his arms eastward into central Asia.

Finally in 539 BC, Cyrus marched triumphantly into the ancient city of Babylon. After this victory, he set the standard of the benevolent conqueror by issuing the Cyrus Cylinder. In this declaration, the king promised not to terrorize Babylon nor destroy its institutions and culture.

- The Cyrus Cylinder is an artifact of the Persian Empire, consisting of a declaration inscribed on a clay barrel. Upon his taking of Babylon, Cyrus the Great issued the declaration, containing an account of his victories and merciful acts, as well as a documentation of his royal lineage. It was discovered in 1879 in Babylon, and today is kept in the British Museum.The royal history given on the cylinder is as follows: The founder of the dynasty was King Achaemenes (ca. 700 BC) who was succeeded by his son Teispes of Anshan. Inscriptions indicate that when the latter died, two of his sons shared the throne as Cyrus I of Anshan and Ariaramnes of Persia. They were succeeded by their respective sons Cambyses I of Anshan and Arsames of Persia. Cambyses is considered by Herodotus and Ctesias to be of humble origin. But they also consider him as being married to Princess Mandane of Media, a daughter of Astyages, King of the Medes and Princess Aryenis of Lydia. Cyrus II was the result of this union.

Cyrus was killed during a battle against the Massagetae or Sakas.

Cyrus' son, Cambyses II, was next in line to rule. When Cyrus conquered Babylon in 539 BC he was employed in leading religious ceremonies (Chronicle of Nabonidus), and in the cylinder which contains Cyrus's proclamation to the Babylonians his name is joined to that of his father in the prayers to Marduk. On a tablet dated from the first year of Cyrus, Cambyses is called king of Babel. But his authority seems to have been quite ephemeral; it was only in 530 BC, when Cyrus set out on his last expedition into the East, that he associated Cambyses on the throne, and numerous Babylonian tablets of this time are dated from the accession and the first year of Cambyses, when Cyrus was "king of the countries" (i.e. of the world). After the death of his father in the spring of 528 BC, Cambyses became sole king. The tablets dated from his reign in Babylonia run to the end of his eighth year, i.e. March 521 BC. Herodotus (3. 66), who dates his reign from the death of Cyrus, gives him seven years five months, i.e. from 528 to the summer of 521.

It was quite natural that, after Cyrus had conquered Asia, Cambyses should undertake the conquest of Egypt, the only remaining independent state of the Eastern world.

Before he set out on his expedition he killed his brother Bardiya (Smerdis), whom Cyrus had appointed governor of the eastern provinces. The date is given by Darius, whereas the Greek authors narrate the murder after the conquest of Egypt. The war took place in 525, when Amasis had just been succeeded by his son Psammetichus III. Cambyses had prepared for the march through the desert by an alliance with Arabian chieftains, who brought a large supply of water to the stations.

King Amasis had hoped that Egypt would be able to withstand the threatened Persian attack by an alliance with the Greeks.But this hope failed the Cypriot towns and the tyrant Polycrates of Samos, who possessed a large fleet, now preferred to join the Persians, and the commander of the Greek troops, Phanes of Halicarnassus, went over to them. In the decisive battle at Pelusium the Egyptians were beaten, and shortly afterwards Memphis was taken. The captive king Psammetichus was executed, having attempted a rebellion. The Egyptian inscriptions show that Cambyses officially adopted the titles and the costume of the Pharaohs, although we may very well believe that he did not conceal his contempt for the customs and the religion of the Egyptians.

From Egypt Cambyses attempted the conquest of Kush, i.e. the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe, located in the modern Sudan. But his army was not able to cross the deserts after heavy losses he was forced to return. In an inscription from Napata (in the Berlin museum) the Nubian king Nastesen relates that he had beaten the troops of Kembasuden, i.e. Cambyses, and taken all his ships (H. Schafer, Die Aethiopische Königsinschrift des Berliner Museums, 1901).

Another expedition against the Siwa Oasis failed likewise, and the plan of attacking Carthage was frustrated by the refusal of the Phoenicians to operate against their kindred.

Death of Cambyses

Meanwhile in Persia a usurper, the Magian Gaumata, arose in the spring of 522, who pretended to be the murdered Bardiya (Smerdis) and was acknowledged throughout Asia. Cambyses attempted to march against him, but, seeing probably that success was impossible, died by his own hand (March 521). This is the account of Darius, which certainly must be preferred to the traditions of Herodotus and Ctesias, which ascribe his death to an accident. According to Herodotus (3.64) he died in the Syrian Ecbatana, i.e. Hamath; Josephus (Antiquites xi. 2. 2) names Damascus; Ctesias, Babylon, which is absolutely impossible.

According to Herodotus, Cambyses sent an army to threaten the Oracle of Amun at the Siwa Oasis. The army of 50,000 men was halfway across the desert when a massive sandstorm sprung up, burying them all. Although many Egyptologists regard the story as a myth, people have searched for the remains of the soldiers for many years. These have included Count Laszlo de Almasy (on whom the novel The English Patient was based) and modern geologist Tom Brown. Some believe that in recent petroleum excavations, the remains may have be uncovered. A 2002 novel by Paul Sussman The Lost Army Of Cambyses recounts the story of rival archaeological expeditions searching for the remains.

The Stone Tablets of Darius the Great

The Persian Rosetta Stone

Seal of Darius the Great

The empire then reached its greatest extent under Darius I. He led conquering armies into the Indus River valley and into Thrace in Europe. His invasion of Greece was halted at the Battle of Marathon.

Darius I, who ascended the throne in 521 BC, pushed the Persian borders as far eastward as the Indus River, had a canal constructed from the Nile to the Red Sea, and reorganized the entire empire, earning the title 'Darius the Great.'

Darius (Greek form Dareios) is a classicized form of the Old Persian Daraya-Vohumanah, Darayavahush or Darayavaush, which was the name of three kings of the Achaemenid Dynasty of Persia: Darius I (the Great), ruled 522-486 BCE, Darius II (Ochos), ruled 423-405/4 BCE, and Darius III (Kodomannos), ruled 336-330 BCE. In addition to these, the oldest son of Xerxes I was named Darius, but he was murdered before he ever came to the throne, and Darius, the son of Artaxerxes II, was executed for treason against his own father.

According to A. T. Olmstead's book History of the Persian Empire, Darius the Great's father Vishtaspa (Hystaspes) and mother Hutaosa (Atossa) knew the prophet Zarathustra (Zoroaster) personally and were converted by him to the new religion he preached, Zoroastrianism.

The empire of Darius the Great extended from Egypt in the west to the Indus River in the east. The major satrapies or provinces of his Empire were connected to the center at Persepolis, in the Fars Province of present-day Iran. The Royal Road connected 111 stations to each other. Messengers riding swift horses informed the king within days of turmoil brewing in lands as distant as Egypt and Sughdiana.

One of the most awe-inspiring monuments of the ancient world, Persepolis was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenian empire. It was built during the reign of Darius I, known as Darius the Great (522-485 BC), and developed further by successive kings. The various temples and monuments are located upon a vast platform, some 450 metres by 300 metres and 20 metres in height. At the head of the ceremonial staircase leading to the terrace is the 'Gateway of All Nations' built by Xerxes I and guarded by two colossal bull-like figures.

Darius was the greatest of all the Persian kings. He extended the empires borders into India and Europe. He also fought two wars with the Greeks which were disastrous.

Darius established a government which became a model for many future governments:

- Established a tax-collection system;

- Allowed locals to keep customs and religions;

- Divided his empire into districts known as Satrapies;

- Built a system of roads still used today;

- Established a complex postal system;

- Established a network of spies he called the "Eyes and Ears of the King."

- Built two new capital cities, one at Susa and one at Persepolis.

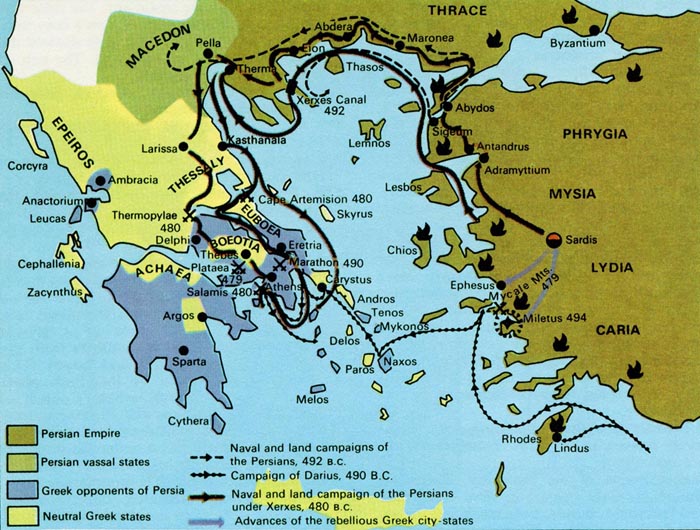

In the 5th century BC the vast Persian Empire attempted to conquer Greece. If the Persians had succeeded, they would have set up local tyrants, called 'satraps', to rule Greece and would have crushed the first stirrings of democracy in Europe. The survival of Greek culture and political ideals depended on the ability of the small, disunited Greek city-states to band together and defend themselves against Persia's overwhelming strength. The struggle, known in Western history as the Persian Wars, or Greco-Persian Wars, lasted 20 years -- from 499 to 479 BC.

Persia already numbered among its conquests the Greek cities of Ionia in Asia Minor, where Greek civilization first flourished. The Persian Wars began when some of these cities revolted against Darius I, Persia's king, in 499 BC.

Athens sent 20 ships to aid the Ionians. Before the Persians crushed the revolt, the Greeks burned Sardis, capital of Lydia. Angered, Darius determined to conquer Athens and extend his empire westward beyond the Aegean Sea.

In 492 BC Darius gathered together a great military force and sent 600 ships across the Hellespont. A sudden storm wrecked half his fleet when it was rounding rocky Mount Athos on the Macedonian coast.

Two years later Darius dispatched a new battle fleet of 600 triremes. This time his powerful galleys crossed the Aegean Sea without mishap and arrived safely off Attica, the part of Greece that surrounds the city of Athens.

The Persians landed on the plain of Marathon, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) from Athens. When the Athenians learned of their arrival, they sent a swift runner, Pheidippides, to ask Sparta for aid, but the Spartans, who were conducting a religious festival, could not march until the moon was full. Meanwhile the small Athenian army encamped in the foothills on the edge of the Marathon Plain.

The Athenian general Miltiades ordered his small force to advance. He had arranged his men so as to have the greatest strength in the wings. As he expected, his center was driven back. The two wings then united behind the enemy. Thus hemmed in, the Persians' bows and arrows were of little use. The stout Greek spears spread death and terror. The invaders rushed in panic to their ships. The Greek historian Herodotus says the Persians lost 6,400 men against only 192 on the Greek side. Thus ended the battle of Marathon (490 BC), one of the decisive battles of the world.

Darius planned another expedition, but he died before preparations were completed. This gave the Greeks a ten-year period to prepare for the next battles. Athens built up its naval supremacy in the Aegean under the guidance of Themistocles.

In 480 BC the Persians returned, led by King Xerxes, the son of Darius. To avoid another shipwreck off Mount Athos, Xerxes had a canal dug behind the promontory. Across the Hellespont he had the Phoenicians and Egyptians place two bridges of ships, held together by cables of flax and papyrus. A storm destroyed the bridges, but Xerxes ordered the workers to replace them. For seven days and nights his soldiers marched across the bridges.

On the way to Athens, Xerxes found a small force of Greek soldiers holding the narrow pass of Thermopylae, which guarded the way to central Greece. The force was led by Leonidas, king of Sparta. Xerxes sent a message ordering the Greeks to deliver their arms. "Come and take them," replied Leonidas.

For two days the Greeks' long spears held the pass. Then a Greek traitor told Xerxes of a roundabout path over the mountains. When Leonidas saw the enemy approaching from the rear, he dismissed his men except the 300 Spartans, who were bound, like himself, to conquer or die. Leonidas was one of the first to fall. Around their leader's body the gallant Spartans fought first with their swords, then with their hands, until they were slain to the last man.

The Persians moved on to Attica and found it deserted. They set fire to Athens with flaming arrows. Xerxes' fleet held the Athenian ships bottled up between the coast of Attica and the island of Salamis. His ships outnumbered the Greek ships three to one. The Persians had expected an easy victory, but one after another their ships were sunk or crippled.

Crowded into the narrow strait, the heavy Persian vessels moved with difficulty. The lighter Greek ships rowed out from a circular formation and rammed their prows into the clumsy enemy vessels. Two hundred Persian ships were sunk, others were captured, and the rest fled. Xerxes and his forces hastened back to Persia.

Soon after, the rest of the Persian army was scattered at Plataea (479 BC). In the same year Xerxes' fleet was defeated at Mycale. Although a treaty was not signed until 30 years later, the threat of Persian domination was ended.

Darius was killed in a coup led by other family members. At the time, he was preparing a new expedition against the Greeks. His son and successor, Xerxes I, attempted to fulfill his plan.

Enthroned in Peresepolis, the magnificent city that he built, Darius I firmly grasps the royal scepter in his right hand. In the left, he is holding a lotus blossom with two buds, the symbol of royalty.

Tomb of Darius

Xerxes

Xerxes was king of Persia from 486-465 BCE. His real name was Ahasuerus. 'Xerxes' is the Greek transliteration of the Persian throne name 'Khshayarsha' or 'Khsha-yar-shan', meaning 'ruler of heroes'. In the Hebrew Bible, the Persian king Ahasuerus in Greek probably corresponds to Xerxes I.

Xerxes I The Great, was the son of Darius I The Great and Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus the Great. He was appointed successor to his father in preference to his eldest half-brother, who were born before Darius had become king.

After his accession in October 485 BC he suppressed the revolt in Egypt which had broken out in 486 BC, appointed his brother Achaemenes as henchman (or khshathrapavan, satrap) bringing Egypt under a very strict rule.

His predecessors, especially Darius, had not been successful in their attempts to conciliate the ancient civilizations. This probably was the reason why Xerxes in 484 BC abolished the Kingdom of Babel and took away the golden statue of Bel (Marduk, Merodach), the hands of which the legitimate king of Babel had to seize on the first day of each year, and killed the priest who tried to hinder him.

Therefore Xerxes does not bear the title of King of Babel in the Babylonian documents dated from his reign, but King of Persia and Media or simply King of countries (i.e. of the world). This proceeding led to two rebellions, probably in 484 BC and 479 BC.

Darius had left to his son the task of punishing the Greeks for their interference in the Ionian rebellion and the victory of Marathon. From 483 Xerxes prepared his expedition with great care: a channel was dug through the isthmus of the peninsula of Mount Athos; provisions were stored in the stations on the road through Thrace; two bridges were thrown across the Hellespont.

Xerxes concluded an alliance with Carthage, and thus deprived Greece of the support of the powerful monarchs of Syracuse and Agrigentum. Many smaller Greek states, moreover, took the side of the Persians, especially Thessaly, Thebes and Argos.

A large fleet and a numerous army (some have claimed that there were over 2,000,000) were gathered. In the spring of 480 Xerxes set out from Sardis. At first Xerxes was victorious everywhere. The Greek fleet was beaten at Artemisium, Thermopylae stormed, Athens conquered, the Greeks driven back to their last line of defence at the Isthmus of Corinth and in the Saronic Gulf.

But Xerxes was induced by the astute message of Themistocles (against the advice of Artemisia of Halicarnassus) to attack the Greek fleet under unfavourable conditions, instead of sending a part of his ships to the Peloponnesus and awaiting the dissolution of the Greek armament.

The Battle of Salamis (September 28, 480) decided the war. Having lost his communication by sea with Asia, Xerxes was forced to retire to Sardis; the army which he left in Greece under Mardonius was in 479 beaten at Plataea. The defeat of the Persians at Mycale roused the Greek cities of Asia.

Of the later years of Xerxes little is known. He sent out Satapes to attempt the circumnavigation of Africa, but the victory of the Greeks threw the empire into a state of slow apathy, from which it could not rise again. The king himself became involved in intrigues of the harem and was much dependent upon courtiers and eunuchs. He left inscriptions at Persepolis, where he added a new palace to that of Darius, at Van in Armenia, and on Mount Elvend near Ecbatana. In these texts he merely copies the words of his father. In 465 he was murdered by his vizier Artabanus who raised Artaxerxes I to the throne.

In the Bible, in the Book of Ezra, Xerxes I is mentioned by the name 'Ashverosh' (Ahasuerus in Greek). It is noted that, during his reign, as in the reign of his predecessor Darius and his successor Artaxerxes, the Samaritans wrote to the Persian king full of accusations against the Jews.Ahasuerus also appears as the King in the Book of Esther, and is traditionally identified with Xerxes.

In the story told in this Biblical book, Ahasuerus dismisses his Queen consort Vashti and then chooses the Jewess Esther as his queen. The king's minister Haman, feeling insulted by Esther's cousin Mordecai, convinces Ahasuerus to decree the destruction of all the Jews in the Persian Empire, but Mordecai and Esther manage to reverse their fate through their influence with the King.

Neither Vashti nor Esther are known from other sources. According to Herodotus, the Queen consort of Xerxes was actually Amestris, daughter to Otanes. Most historians consider the 'Book of Esther' to be a historical fiction, and assume that the events depicted therein did not actually occur.

Artaxerxes continued building work at Persepolis. It was completed during the reign of Artaxerxes III, around 338 BC. In 334 BC, Alexander the Great defeated the Persian armies of the third Darius. He marched into Iran and, once there, he turned his attention to Persepolis, and that magnificent complex of buildings was burnt down. This act of destruction for revenge of the Acropolis, was surprising from one who prided himself on being a pupil of Aristotle. This was the end of the Persian Empire.

Xerxes's Hall of the 100 Columns is the most impressive building in the complex. It is also the most crowded--a jumble of fallen columns, column heads, and column bases.

The Gate of Xerxes at Perespolis shows that the Winged Lion was placed at the corner of one entrance. When you stood in front of the gate you saw a lion with four legs and when you were inside the gate you also saw a lion with four legs.

The later years of the Achaemenid dynasty were marked by decay and decadence. The mightiest empire in the world collapsed in only eight years, when it fell under the attack of a young Macedonian king, Alexander the Great.

Alexander was born in Macedon, a province of ancient Greece, in 356 B.C. He seemed destined at a young age for power. He assumed the throne of Macedon at the young age of twenty. At the age of twenty-two he attacked and conquered the Greek-occupied portion of the Achaemenid Empire, unifying the territories and becoming the great king of Greece. He then peacefully acquired most of Egypt and was made a pharaoh, which to the Egyptians meant he was the son of a god, therefore like a god himself.

Persia's weakness was exposed to the Greeks in 401 BC, when the Satrap of Sardis hired ten thousand Greek mercenaries to help secure his claim to the imperial throne. This exposed both the political instability and the military weakness of late Achaemenid Persia.

Philip II of Macedon, leader of most of Greece, and his son Alexander the Great decided to take advantage of this weakness. After Philip's death, Alexander set his sights on Persia, possibly for reasons of protection for Greece but mainly just for conquest.

Any doubts Alexander might have had about the success of his Persian campaign were put to rest when he consulted the Oracle at Delphi, who told him, "Thou art invincible, my son."

Alexander's army landed in Asia Minor in 334 BC. His armies quickly swept through Lydia, Phoenicia, and Egypt, before defeating all the troops of Darius III at Issus and capturing the capital at Susa.

The last Achaemenid resistance was at the "Persian Gates" near the royal palace at Persepolis. The Persian Empire was now in Greek hands.

Along the way he exercised such faculties as sharp intellect, discernment, knowledge of warfare and politics, and human nature. He treated his generals well and commanded their respect.

However in spite of being admired for his generosity, mastery, and loyalty, he was feared for his terrible temper. He once caught a traitorous lieutenant and cut off his ears and nose before killing him. He even slew one of his most capable generals and a loyal friends, Cleitus, over a drunken misunderstanding.

Alexander rapidly conquered Persia and declared himself the lord of Asia. He adopted a policy of fusion between his own kingdom of Greece and the vanquished Persia. He left the previous Persian rulers in control whenever possible.

Along his route of conquest, Alexander founded many colony cities, all named "Alexandria". For the next several centuries, these cities served to greatly extend Greek, or Hellenistic, culture in Persia.

He encouraged the flow of ideas, customs, and even preferred a Persian style of dress, and took a Persian wife Roxanne. Alexander's conquests, in addition to bringing him great fame and untold riches.

The historian Callisthenes began a rumor asserting that Alexander was the son of Zeus, significantly contributed and enriched Greek and Western culture in the areas of thought, science generally and specifically founded at least sixeteen cities, created new coinage, and pioneered methods for ruling and administrating government.

Alexander's next and final conquest would be what is now known as India. He began in 327 B.C. and eventually acquired a significant portion. Alexander dreamed of continuing eastward where he hoped to find a great eastern ocean. But facing a minor political disturbance at home, he returned to Greece in 324 B.C. and died in 323 B.C. of fever due to exhaustion and wounds recieved in previous battles, leaving his dream unfulfilled. He was thirty-two years old and had ruled for twelve years and eight months.

Alexander had succeeded, as Columbus did much later, in opening up a new world for western culture. Alexander amassed a territory from Greece to the Caspian sea. He was unquestionably the strongest power that the world at that point had ever seen. He seemed to be able to do just as he wished. He was one part realist and one part visionary and excelled at making war.

Alexander's empire broke up shortly after his death, but Persia remained in Greek hands. Alexander's general, Seleucus, took control of Persia, Mesopotamia, and later Syria and Asia Minor.

Greek colonization continued until around 250 BC; Greek language, philosophy, and art came with the colonists. Throughout Alexander's former empire, Greek became the common tongue of diplomacy and literature.

Trade with China had begun in Achaemenid times along the so-called Silk Road; but during the Hellenistic period it began in earnest. The overland trade brought about some fascinating cultural exchanges.

Buddhism came in from India, while Zoroastrianism traveled west to influence Judaism. Incredible statues of the Buddha in classical Greek styles have been found in Persia and Afghanistan, illustrating the mix of cultures that occurred around this time, although it is possible that Greco-Buddhist art dates from Achaemenid times when Greek artists worked for the Persians.

The Seleucid kingdom began to decline rather quickly. Even during Seleucus' lifetime, the capital was moved from Seleucia in Mesopotamia to the more Mediterranean-oriented Antioch in Syria.

The eastern provinces of Bactria and Parthia broke off from the Seleucid Kingdom in 238 BC.

King Antiochus III's military leadership kept Parthia from overrunning Persia itself, but his successes alarmed the burgeoning Roman Empire. Roman legions began to attack the kingdom.

At the same time, the Seleucids had to contend with the revolt of the Maccabees in Judea and the expansion of the Kushan Empire to the east.

The empire fell apart and was conquered by Parthia and Rome.

Metallic statue of a Parthian prince (thought to be Surena), AD 100,

kept at The National Museum of Iran, Tehran.

Parthia was a region north of Persia in what is today northeastern Iran. Its rulers, the Arsacid dynasty, belonged to an Iranian tribe that had settled there during the time of Alexander. They declared their independence from the Seleucids in 238 BC, but their attempts to expand into Persia were thwarted until c. 170 BC under Mithridates I.

The Parthian Empire shared a border with Rome along the upper Euphrates River. The two empires became major rivals. Parthian mounted archers proved a match for Roman legions, as in the Battle of Carrhae in which the Parthian General Surena defeated Crassus of Rome. Wars were very frequent, with Mesopotamia serving as the battleground.

During the Parthian period, Hellenistic customs partially gave way to a resurgence of Persian culture. However, the empire lacked political unity. By the first century BC, Parthia was decentralized, ruled by feudal nobles.

Wars with Rome to the west and the Kushan Empire to the northeast drained the country's resources.

Parthia, now impoverished and without any hope to recover the lost territories, was demoralized. The kings had to give more concessions to the nobility, and the vassal kings sometimes refused to obey.

In AD 224, the Persian vassal king Ardashir revolted. Two years later, he took Ctesiphon, and this time, it meant the end of Parthia. It also meant the beginning of the second Persian Empire, ruled by the Sassanid kings.

Head of king Shapur II (Sasanian dynasty 4th century AD).

During Parthian rule, Persia was only one province in a large, loosely controlled empire. The local king of Persia at this time, Ardashir I, led a revolt against the imperial government of Parthia. In two years he was the shah of a new Persian Empire.

The Sassanid (or Sassanian) dynasty (named for Ardashir's grandfather) was the first native Persian ruling dynasty since the Achaemenids; thus they saw themselves as the successors of Darius and Cyrus. They pursued an aggressive expansionist policy. They recovered much of the eastern lands that the Kushans had taken in the Parthian period. The Sassanids continued to make war against Rome; a Persian army even captured the Emperor Valerian in 260.

Sassanid Persia, unlike Parthia, was a highly centralized state. The people were rigidly organized into a caste system: Priests, Soldiers, Scribes, and Commoners. Zoroastrianism was finally made the official state religion, and spread outside Persia proper and out into the provinces. There was sporadic persecution of other religions. The Catholic (Orthodox) Christian church was particularly persecuted, but this was in part due to its ties to the Roman Empire. The Nestorian Christian church was tolerated and sometimes even favored by the Sassanids.

The wars and religious control that had fueled Sassanid Persia's early successes eventually contributed to its decline. The eastern regions were conquered by the White Huns in the late 400s. Adherents of a radical religious sect, the Mazdakites, revolted around the same time. Khosrau I was able to recover his empire and expand into the Christian countries of Antioch and Yemen. Between 605 and 629, Sassanids successfully annexed Levant and Egypt and pushed into Anatolia.

However, a subsequent war with the Romans utterly destroyed the empire. In the course of the protracted conflict, Sassinid armies reached Constantinople, but could not defeat the Byzantines there. Meanwhile, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius had successfully outflanked the Persian armies in Asia Minor and handed them a crushing defeat in Northern Mesopotamia. The Sassanids had to give up all their conquered lands and retreat. This defeat was mentioned in Qur'an as a "victory for believers," referring to the Romans, who were monotheists, in contrast to the pagan Sassinids.

Heavy taxes caused by the very long war caused rebellions across the empire, and the Emperor Khosro II (Parviz) was assassinated in 629. This incident was allegedly fortold by Muhammed as a punishment from God because Khosro humiliated Muhammed's messangers and tore a message from the Prophet which contained a chapter of Qur'an. After a defeat at Nineveh in 642, Khosro's successor Kavdah II was also assassinated. Civil war broke out across the Empire and the country descended into anarchy.

The explosive growth of the Arab Caliphate coincided with the chaos caused by the end of Sassanid rule. Conquest came easily; most of the country was overrun in 643-650. The last resistance from the remnants of the Sassanid dynasty ended two years later.

Persia's conquest by Islamic Arab armies marks the transition into "medieval" Persia.

Yazdagird III, the last Sasanian King, died ten years after he lost his empire to the newly-formed Muslim Caliphate. He tried to recover some of what he lost with the help of the Turks and the Tatars but they were easily defeated by Muslim armies. Then he seeked the aid of the Chinese but they refused to help him. He is believed to have lived on the borders of the Islamic Persia. Some historians say that he lived inside the Islamic Persia.

The Arab empire, ruled by the Umayyad Dynasty, was the largest state in history up to that point. It stretched from Spain to the Indus, from the Aral Sea to the southern tip of Arabia. Yet the Umayyads borrowed heavily from Persian and Byzantine administrative systems and moved their capital to Damascus, in the center of their empire. The Umayyads would rule Persia for a hundred years.

The Arab conquest dramatically changed life in Persia. Arabic became the new lingua franca and Islam quickly replaced Zoroastrianism; mosques were built, and many Persians intermarried with Arabs. A new language, religion, and culture were added to the Persian cultural milieu.

In 750 the Umayyads were ousted from power by the Abbasid family. By that time, Iranians had come to dominate not only the bureacracy of the empire, but all branches of the government. The unrivaled dominance of the Persians on all affairs of the administration of the Caliphate led to the spread and blossoming of Persian culture, science, mathematics, and medicine, throughout the Arab world.

The caliph Al-Ma'mun, whose mother was an Iranian, moved his capital away from Arab lands into Merv in eastern Persia. It was he who later founded the Baghdad House of Wisdom, based on the Persian Jondishapour.

The scientific movement that resulted from this was to have a direct impact on the European Renaissance centuries later: the Iranian Khwarazmi contributed heavily to the mathematical field of algebra, earning himself the title of Father of Algebra. He, along with hundreds of other prominent scholars, carried the torch of the world's most advanced civilizations for hundreds of years.

But political unrest continued. In 819, East-Persia was conquered by the Persian Samanids, the first native rulers after the Arabic conquest. They made Samarqand, Bukhara and Herat their capitals and revived the Persian language and culture.

It was approximately during this age, when the poet Firdawsi finished the Shah Nama, an epic poem retelling the history of the Persian kings; Firdawsi completing the poem in 1008.In 913, West-Persia was conquered by the Buwayhid, a native Persian tribal confederation from the shores of the Caspian Sea.

They made the Persian city of Shiraz their capital. The Buwayids destroyed Islam's former territorial unity. Rather than a province of a united Muslim empire, Persia became one nation in an increasingly diverse and cultured Islamic world.

The Muslim world was shaken again in 1037 with the invasion of the Seljuk Turks from the northeast. The Seljuks created a very large Middle Eastern empire and continued in the flowering of medieval Islamic culture.

The Seljuks built the fabulous Friday Mosque in the city of Isfahan.

The most famous Persian writer of all time, Omar Khayyam, wrote his Rubayat of love poetry during Seljuk times.

In the early 1200s the Seljuks lost control of Persia to another group of Turks from Khwarezmia, near the Aral Sea. The shahs of the Khwarezmid Empire ruled for only a short while, however, because they had to face the most feared conqueror in history: Genghis Khan.

In 1218, Genghis Khan sent ambassadors and merchants to the city of Otrar, on the northeastern confines of the Khwarizm shahdom. The governor of Otrar had these envoys executed. Genghis, out of revenge, sacked Otrar in 1219 and continued on to Samarkand and other cities of the northeast.

Genghis' grandson, Hulagu Khan, finished what Genghis had begun when he conquered Persia, Baghdad, and much of the rest of the Middle East in 1255-1258. Persia became the Ilkhanate, a division of the vast Mongol Empire.

In 1295, after Ilkhan Ghazan converted to Islam, he renounced all allegiance to the Great Khan. The Ilkhans patronized the arts and learning in the fine tradition of Persian Islam; indeed, they helped to repair much of the damage of the Mongol conquests.

In 1335, the last Ilkhan's death spelled the end of the Ilkhanate. It splintered into a number of small states. This left Persia open to still more conquest at the hands of another conqueror connected with the Mongol Empire: Timur the Lame or Tamerlane. He invaded Persia beginning around 1370 and plundered the country until his death in 1405.

Timur was an even bloodier conqueror than Genghis had been. In Isfahan, for instance, he slaughtered 70,000 people so that he could build towers with their skulls. He conquered a wide area and made his own city of Samarkand rich, but he made no effort to forge a lasting empire. Persia was essentially left in ruins.

For the next hundred years Persia was not a unified state. It was ruled for a while by descendants of Timur, called the Timurid emirs. Toward the end of the 1400s, Persia was taken over by the Emirate of the White Sheep Turkmen (Ak Koyunlu). But there was little unity and none of the sophistication that had defined Persia during the glory days of Islam.

The Safavid Dynasty hailed from Azerbaijan, at that time considered a part of the greater Persia region. The Safavid Shah Ismail I overthrew the White Sheep Turkish rulers of Persia to found a new native Persian empire. Ismail expanded Persia to include all of present-day Azerbaijan, Iran, and Iraq, plus much of Afghanistan.

Ismail's expansion was halted by the Ottoman Empire at the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, and war with the Ottomans became a fact of life in Safavid Persia.

Safavid Persia was a violent and chaotic state for the next seventy years, but in 1588 Shah Abbas the Great ascended to the throne and instituted a cultural and political renaissance.

He moved his capital to Isfahan, which quickly became one of the most important cultural centers in the Islamic world. He made peace with the Ottomans. He reformed the army, drove the Uzbeks out of Persia and into modern-day Uzbekistan, and captured a Portuguese base on the island of Ormus.

The Safavids were followers of Shi'a Islam, and under them Persia became the largest Shi'ite country in the Muslim world, a position Iran still holds today.

Under the Safavids Persia enjoyed its last period as a major imperial power. In the early 1600s, a final border was agreed upon with Ottoman Turkey; it still forms the border between Turkey and Iran today.

In 1722, Safavid Persia collapsed. That year saw the first European invasion of Persia since the time of Alexander: Peter the Great, Czar of Russia, invaded from the northwest as part of a bid to dominate central Asia. To make the situation truly hopeless, Ottoman forces accompanied the Russians, successfully laying siege to Isfahan.

The country was able to weather the invasions; neither the Russians nor the Turks gained any territory. However, the Safavids were severely weakened, and that same year (1722), the empire's Afghani subjects launched a bloody revolt in response to the Safavids' attempts to convert them from Sunni to Shi'a Islam by force. The last Safavid shah was executed, and the dynasty came to an end.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the natural philosophy and mathematics of ancient Greeks were furthered and preserved within the Muslim world. During this period, Persia became a centre for the manufacture of scientific instruments, retaining its reputation for quality well into the 19th century.

The Persian empire experienced a temporary revival under Nadir Shah in the 1730s and '40s. Nadir drove out the Russians and confined the Afghans to their present home in Afghanistan. He launched many successful campaigns against Persia's old enemies, the nomadic khanates of Central Asia; most of them were destroyed or absorbed into Persia. However, his empire declined after his death. His rule was followed by the weak and short-lived Zand dynasty. Persia was left unprepared for the worldwide expansion of European empires in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Persia found relative stability in the Qajar dynasty, ruling from 1779 to 1925, but lost hope to compete with the new industrial powers of Europe; Persia found itself sandwiched between the growing Russian Empire in Central Asia and the expanding British Empire in India. Each carved out pieces from Persia that became Bahrain, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenia, Tajikestan, Uzbekistan, and parts of Afghanistan.

Although Persia was never directly invaded, it gradually became economically dependent on Europe. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 formalised Russian and British spheres of influence over the north and south of the country, respectively, where Britain and Russia each created a "sphere of influence", where the colonial power had the final "say" on economic matters.At the same time the young Shah had granted a concession to William Knox D'Arcy, later the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, to explore and work the newly-discovered oil fields at Masjid-al-Salaman in southwest Persia, which started production in 1914. Winston Churchill, as First Sea Lord to the British Admiralty, oversaw the conversion of the Royal Navy to oil-fired battleships and partially nationalized it prior to the start of war. A small Anglo-Persian force was garrisoned there to protect the field from some hostile tribal factions.

Persia was drawn into the periphery of WWI because of its strategic position between Afghanistan and the warring Ottoman, Russian, and British Empires. In 1914 Britain sent a military force to Mesopotamia to deny access to the Persian oilfields from the Ottomans. Germany retaliated on behalf of its ally by spreading a rumour that the Kaiser had converted to Islam, and sent agents through Persia to attack the oil fields and raise a Jihad against British rule in India. Most of those German agents were captured by Persian, British and Russian troops who were sent to patrol the Afghan border, and the rebellion faded away.

This was followed by a German attempt to abduct and control the young Shah, with the assistance of his mainly-Swedish bodyguard, which was foiled at the last moment.

In 1916 the fighting between Russian and Ottoman forces to the north of the country had spilt down into Persia; Russia gained the advantage until most of her armies collapsed in the wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution.

This left the Caucasus unprotected, and the Caucasian and Persian civilians starving after years of war and depravation. In 1918 a small force of 400 British troops under General Dunsterville moved into the Trans-Caucasus from Persia in a bid to encourage local resistance to German and Ottoman armies who were about to invade the Baku oilfields.

Although they later withdrew back into Persia, they did succeed in delaying the Turks access to the oil almost until the Armistice. In addition, the expedition¹s supplies were used to avert a major famine in the region, and a camp for 30,000 displaced refugees was created near the Persian-Mesopotamian border.

By WW1 Persia was not the world power it had once been; it had become a tool in the political battles of other empires.In 1919 northern Persia was occupied by the British General Edmund Ironside to enforce the Turkish Armistice conditions and assist General Malleson contain Boshevik influences in the north. Britain also took tighter control over the increasingly lucrative oilfields.

In 1925, Reza Shah Pahlavi seized power from the Qajars and established the new Pahlavi dynasty. However, Britain and the Soviet Union remained the influential powers in Persia into the early years of the Cold War.The second-to-last Shah, Reza Pahlavi, asked the world to call the country Iran in 1935, but in 1959 Mohammad Reza Pahlavi announced that both Persia and Iran can be used interchangeably.

References and Links:

Persian Empire Wikipedia

In the News ...

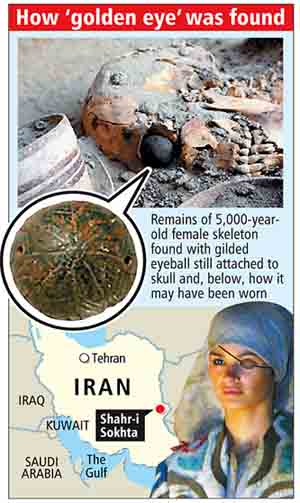

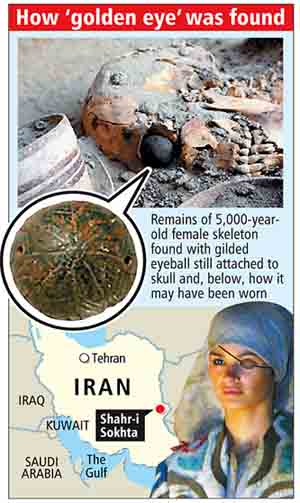

- Daily Mail - February 22, 2007The body of a strikingly tall 5,000-year-old woman with an artificial golden eye has been discovered in Iran. Archaeologists said the woman was a female soothsayer or priestess and would have transfixed those around her with her eyeball, making them believe she had occult powers and could see into the future. The 25-30-year old Persian woman, who was almost 6 feet tall, was also buried with an ornate bronze hand mirror so she could check her startling appearance. The golden eyeball is engraved with lines coming out of a central circle like rays of light.

Cylindrical Seal with a Strange Design Discovered in Dezful CHN - May 31, 2006

Cultural Heritage News Agency - Tehran, May 28, 2006

Archeological excavations in Sanjar Tepe in Khuzestan province resulted in discovery of a cylindrical seal with the design of a winged horse on its end.

Although it is not the first time archeologists are confronted with the design of a winged horse in Iran, what makes this one special compared to the previous ones is that this winged horse has a lion's head and a cow or a goat's hooves, creating a strange creature which combines features of a horse, a bird, a lion, and a cow!

A stone seal which most probably belongs to the Sassanid era (226-651 AD) was discovered during the first archeological excavation in Sanjar Tepe in Dezful.

The design of a winged horse can be seen on the seal whose head is like a lion and has round hooves like a cow or a goat. Horse was considered as a sacred animal during the Sassanid period and had a special place among the Persians of the time. We had previously found a large number of Sassanid seals with the designs of winged horses on them in other archeological sites but what makes this one unique among all the pervious ones is that it is the first time we see such a strange combination of four animals all in one.

Another interesting thing about this design is that the hooves are round not cracked, although we don¹t have any idea about the reason it is designed so,² said Mostafa Abdolahi, archeologist and head of Archeology Department of Azad University of Dezful. First season of archeological excavations in Sanjar Tepe has started by the students of Dezful Azad University under the supervision of Dr. Pour Derakhshandeh.

According to Abdolahi, the objects which have been discovered so far in this historical site, including clay, bronze and iron relics, were displayed in an exhibition in Khuzestan which was held during the Cultural Heritage Week (18-25 of May). "Some models illustrating the Islamic architectural style used in the constructions of the city and colored posters from some historic monuments prepared by the students were displayed in this exhibition. In addition, some documentary movies from different archeological sites were screened in this exhibition," said Abdolahi.

Sanjar historical Tepe is located in the city of Dezful in Khuzestan province, south of Iran, and belongs to the Elamite period (2700 BC-539 BC). The first season of archeological excavations in this historical site led to discovery of the location of Zahari, the Elamite city. ³This city was located between the cities of Susa and Avan.

Cultural Heritage News Agency - October 13, 2005

The recent excavations in Rabat Teppe archaeological site in Sardasht, Northwestern Iran, led to discovery of four icons of winged goddesses on bricks which belong to 3000 years ago. These are the first ever winged goddesses found in Iran. In initial measures, the area of the archaeological site was believed to be 14 hectares but recent studies extend its measures to 25 hectares.

"This season of the excavations has led to discovery of four winged goddesses in Rabat Teppe which can be traced back to the Iron Age, about 3000 years ago. This kind of icons has never been seen in any Iranian archaeological site before," said Reza Heydari, an archaeologist of Western Azarbaijan Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization. "These icons are unique and have no counterpart even in Persepolis. In Persepolis there is no sign of women," he added. "The found icons are women with haunches that are similar to deer or cow. Each one of the four goddesses has 2 raised wings."

The most outward level of the site belongs to the first millennium BC. The archaeologists¹ excavation which was started in current year September is an effort for a comparison of the site to the Mushashir's civilization. Based on historical documents, one of the biggest ancient religion¹s temples was based in the location. Mushashir civilization was contemporary with Urartu and Assyria. Due to political situations, Mushashirs sometimes allied with Assyrians or Urartu people.

Ziggurat in Iraq - Teppe Sialk

Ziggurat in Iraq - Teppe Sialk